Sandro Đukić and Bojan Salaj: Archive as a Memory Construct Memory as the Construct of Present – Day Social Discourses

27.7.–27.9.2021.

A map of the world that does not include Utopia is not worth even glancing at, for it leaves out the one country at which Humanity is always landing. And when Humanity lands there, it looks out, and, seeing a better country, sets sail. Progress is the realization of Utopias. Oscar Wilde

In 1988, multimedia artist Sandro Đukić began creating nonutilitarian objects. He made them of an artificial material – Ultrapas, with the addition of electronics, photographs, paintings, and drawings. As key artistic questions which he relates to this period of his artistic activity, he notes the issue of the media and surmounting the period’s artistic formalism, as well as the issue of implementing artistic objects so that they seem impersonal and industrially-made. Discarding the old makes way for the new, while the idea of the new makes way for imagining Utopia. Following a series of smaller-scale exhibitions, in 1991, together with Damir Babić, he implemented the exhibition project simply entitled Objects at HAZU Glyptotheque, at which he exhibited the entire series. Alongside the artist’s works, theoretician Krešimir Purgar wrote the comprehensive essay An Object’s Double Reality, published in the exhibition catalogue.

Upon seeing for the first time Sandro Đukić’s objects from the early 1990s, I remember my astonishment that something like that had been presented in Zagreb in those years, and that it was possible even to produce such an exhibition. This was the time of onset of armed conflicts in the now former state; save for defence of the country, the beginning of the war also saw the all-encompassing political and economic reform. Who would even think of art at that time? With the passing of years, dust seems to have been additionally depositing and blurring the view. The only thing that was clear and that we are aware of even today is that the 1990s were a clean cut – an interruption in continuity, years in which people and events were vanishing in the whirlwind of war. Erasure of the old and conception of the new. The new states, created by the disintegration of Yugoslavia, built their identities in strong opposition towards everything that had hitherto been common – common culture, history, and technological development. For a while now, however, there exists a desire to re-examine the 1990s, to also add to the official narratives of heroism and war sacrifice the voices of those who lived and created in this period, to breathe life into the petrified armour and to detect traces along which we arrived at the present point. One of the questions is therefore also the one of art or, more precisely – which from the 1990s art is also effective today?

My interest in Đukić’s objects favourably coincided with his desire to pull them out of oblivion and examine whether they have even left a mark on the domestic art scene. Therefore, we began the project by recollecting – with Đukić’s memories on the circumstances of the period, the coming-of-age of his generation, the clique with whom he exchanged thoughts and ideas. He also remembered the circumstances of the objects’ creation and the role of Bojan Salaj, the significance of the exhibition with which they had presented themselves to Zagreb’s audience, the physical destruction of all exhibits following its closing, as well as the reconstruction of two selected pieces, one of which would go on to win First Prize at the final 16th Biennale of Young Yugoslav Artists in Rijeka; the beginning of war, the destruction of reconstructed objects. The question we returned to again and again was related to possibility – the possibility to imagine, the possibility to work and collaborate, the possibility to (re)construct history, the lack of possibilities, the impossibility of continuity. Something that was called a view towards the west at the time of its creation became over time a synonym for a lost future, for a time in which Utopia was still imaginable. The 1990s generation, a member of which is also Đukić himself, grew and debuted at the very moment prior to the collapse of the familiar world, only to be followed by vacuum and self-imposed (national) oblivion. Their artistic insights and efforts were collateral victims of time, spectacularly forgotten as they simply did not fit into the image of the new state’s culture.

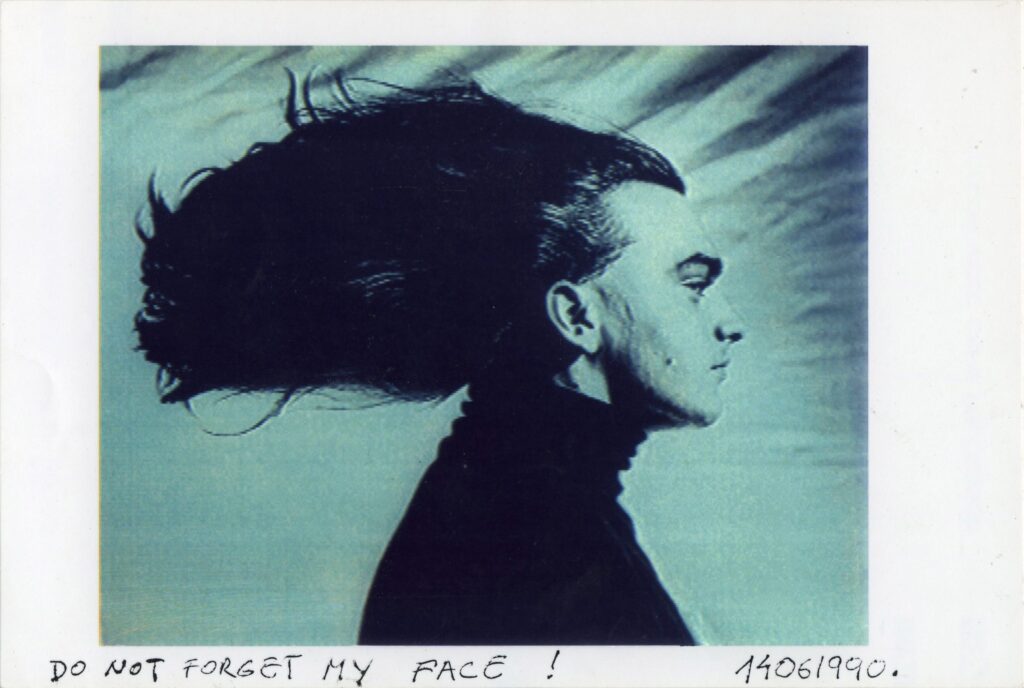

The project Archive as a Memory Construct was first presented in 2019. For this occasion, Đukić reconstructed the object awarded at Rijeka’s Youth Biennale, which was then shown to the audience of Zagreb at Spot Gallery. The reconstructed object is formed as a horizontal cuboid and is made up of three segments: a “self-portrait” (a directed portrait of young Đukić photographed by Salaj), a black cuboid, and a segment made of Ultrapas with a digital clock showing sans punctuation spaces the year, month, day, hour, second, tenth of a second. The concept of this, as well as of other objects is theoretically based in the texts by Jean Baudrillard, Gilles Deleuze, Slavoj Žižek and others, and is strongly oriented towards the subject’s position in a post-ideological society. The use of Ultrapas, a material that imitates natural substances, accentuates the uncertainty of time in which the objects were created, while digital clocks actually represent merely an abstract number. A special place in Đukić’s imaginarium belongs to the film Blade Runner (to which he would also refer in his later works) and to Philip K. Dick, the science fiction writer whose work Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? served as a template for said film; Đukić refers to it by creating replicants of himself through multiplying own portraits and creating a world of objects. The view aimed towards the west is nevertheless not non-critical – what can be interpreted are the references to consumerism, the society of the spectacle, the loss of individualism and sense for historical past and historical futures (Jameson).

The reconstructed object is the imaginary centre of this exhibition and has actually been given a double role. On the one hand, it is treated as a historic artefact and is accompanied as such by the documentation of the period – sketches, photographs, related works, newspaper articles, letters. Save for the documentation, there is also a series of video interviews with protagonists of the period – artists and curators, who remember the exhibition at the Glyptotheque, as well as the context of time. The contextualisation is also contributed by the works of Bojan Salaj. Alongside the works produced in the early 1990s for the needs of other artists, there are also his photographs of television reports from 1992, showing the war suffering in Bosnia and Hercegovina.

The second role of the object is that of a time machine. In the past in which there exist the future and Utopia to which we aspire, it is possible to travel through time. The inconvenient thing about the future, however, is that it can fulfil, but also betray expectations – namely, what if we realise that, instead of the imagined Utopia, anti-Utopia awaits us? About thirty years into the future, it is evident that the West has failed to deliver the promise of a more righteous society and a better life. In the period of late capitalism, transitional post-socialist countries find themselves on a capitalist periphery. The process of transition to a capitalist economic model included waves of privatisation and deindustrialisation, and selling of socialist industrial giants for a mere trifle. This is exactly what is shown in Sandro Đukić’s work Ironworks (2017) – a typical transitional story that is specific insofar as that the devastation of the factory caused the shrinking of the city. The residential complexes built by the factory, which once swarmed with workers of Sisak Ironworks and their families, are now merely abandoned edifices of the shrinking city.

The permeable sites on the hegemonic seam (Bekić) are an anti-Utopian reality in which the system’s recurring violence has led to entropy in society. In relation to the disenfranchised workers, the positions of power are to be found somewhere further to the west. With his work Interiors-Correspondences (2014), Bojan Salaj leads us to the heart of anonymous bureaucracy, in the centre of political power that shapes our world, the conference hall of the European Parliament.

The anonymity of human fates (Salaj, P2020 / Spirit is a Soul) is contradicted by that of our time traveller – artist who is now 30 years older. With a self-ironic distance, Đukić shows us himself (Natura Morta, 2019), tired and disheartened in a decrepit ambience of an abandoned space. Previous wellbeing can only be intuited.

Science Fiction is generally understood as the attempt to imagine unimaginable futures. But its deepest subject may in fact be our own historical present. Frederic Jameson

Lana Lovrenčić

Translated by Mirta Jurilj

Curator: Lana Lovrenčić

Exhibition set-up: Sandro Đukić, Lana Lovrenčić, Bojan Salaj

Technical set-up: Casa Grad d.o.o., Vedran Grladinović, IM-Exordium Prom j.d.o.o.

Exhibition assistant: Sabina Salamon

Exhibition opening: 27. 7. at 8.30 pm

Sandro Đukić, Do not forget my face! (autoportret), 1990